Lekár Ignacio Girolimini miluje psy.

Fotografie zámien čakajúcich na prijatie na jeho Facebooku sa rozptýlia s príspevkami o tom, kde získať vakcínu proti chrípke a zdieľajú sa v mene skupiny, ktorá získava finančné prostriedky pre miestnu nemocnicu.

Začiatkom roka 2023 však Dr. Girolimini požiadal 25 000 obyvateľov San Miguel del Monte – chcel, aby sa zúčastnili prieskumu o povedomí o mozgovej príhode. Prieskum bol súčasťou projektu na zriadenie apoplexie v nemocniciZenón Videla Dorna Hospital, ktorú vysvetlil vo videu zdieľanom 17. februára. O desať dní neskôr by tento projekt zachránil život a zmenil budúcnosť starostlivosti o mozgovú príhodu v tomto pokojnom vidieckom meste.

Liečba akútnej ischemickej cievnej mozgovej príhody bola vždy na radare Dr. Grioliminiho. Bol to dôvod, prečo sa v roku 2021 zaregistroval v iniciatíve Angels Initiative a absolvoval takmer všetky e-learningové kurzy v akadémii Angels Academy – od kurzu ASLS pre lekárov EMS až po základy mozgovej príhody pre zdravotné sestry. Z tohto dôvodu sa zúčastnil mentorského programu ROPU, prostredníctvom ktorého sa spojil s Dr. Claudiom Jiménezom, neurológom v diamantovo získanej nemocnici SimónBolívar Hospital v Bogote v Kolumbii, a spoznal Anjelsov tím v provincii Buenos Aires.

Náustkový bod prišiel v júni 2022 akvizíciou CT skenera pre 124-ročnú nemocnicu San Miguel del Monte. Pre Dr. Giroliminiho, ktorý bol okamihom pri liečbe akútnej cievnej mozgovej príhody, prestal byť zámerom a stal sa povinnosťou.

Ignacio Girolimini bol vychovaný v San Miguel del Monte, kde sa život nachádza okolo 720-hektárovej lagúny tak krásnej, že má svoj vlastný účet na Instagrame. Je prvým lekárom vo svojej rodine a keď prvýkrát odišiel na štúdium na University of Buenos Aires a neskôr sa špecializoval na internú medicínu, očakával, že príde na príležitostný víkend. Napriek tomu, že rád pracoval vo veľkom kozmopolitnom hlavnom meste, nemal rád dopravné zápchy a vynechal lagúnu, svoju rodinu a pokoj života v malom meste.

V roku 2020 prišiel domov do jedinej nemocnice San Miguel del Monte s cieľom „vynikajúci spôsob starostlivosti o potreby nášho malého mesta“.

S najbližšou nemocnicou pripravenou na mŕtvicu boli obyvatelia San Miguel del Monte na rovnakej lodi ako väčšina Argentíncov žijúcich ďaleko od veľkých miest. Pacienti s cievnou mozgovou príhodou vrátane starej mamy Dr. Giroliminiho boli efektívne ponechaní na osud, pretože veľké vzdialenosti a nízke uvedomenie znamenali, že len málo pacientov dosiahlo akútnu liečbu včas.

Dr. Girolimini, ktorý nasadil úplne nový CT skener a s podporou riaditeľov nemocníc, začal pracovať na protokole o mozgovej príhode pre svoju nemocnicu, čo je proces, ktorý zhromaždil rýchlosť po tom, ako anjelská poradkyňa Daiana Michel navštívila San Miguel del Monte na 1. február 2023. Cesta, ktorú navrhli, sa sústredila okolo nového skenera CT – bola tam, kde by pohotovostné služby priniesli pacientov s podozrením na cievnu mozgovú príhodu a kde, ak by pacient spĺňal podmienky, začala by sa liečba. Ale aby sa zabezpečilo, že pacienti prídu včas, populácia musela byť poučená o mozgovej mŕtvici, a to je to, o čom bol prieskum Dr. Girolimini.

„O chvíľu môžete stratiť dva milióny neurónov,“ začala sa jeho video správa...

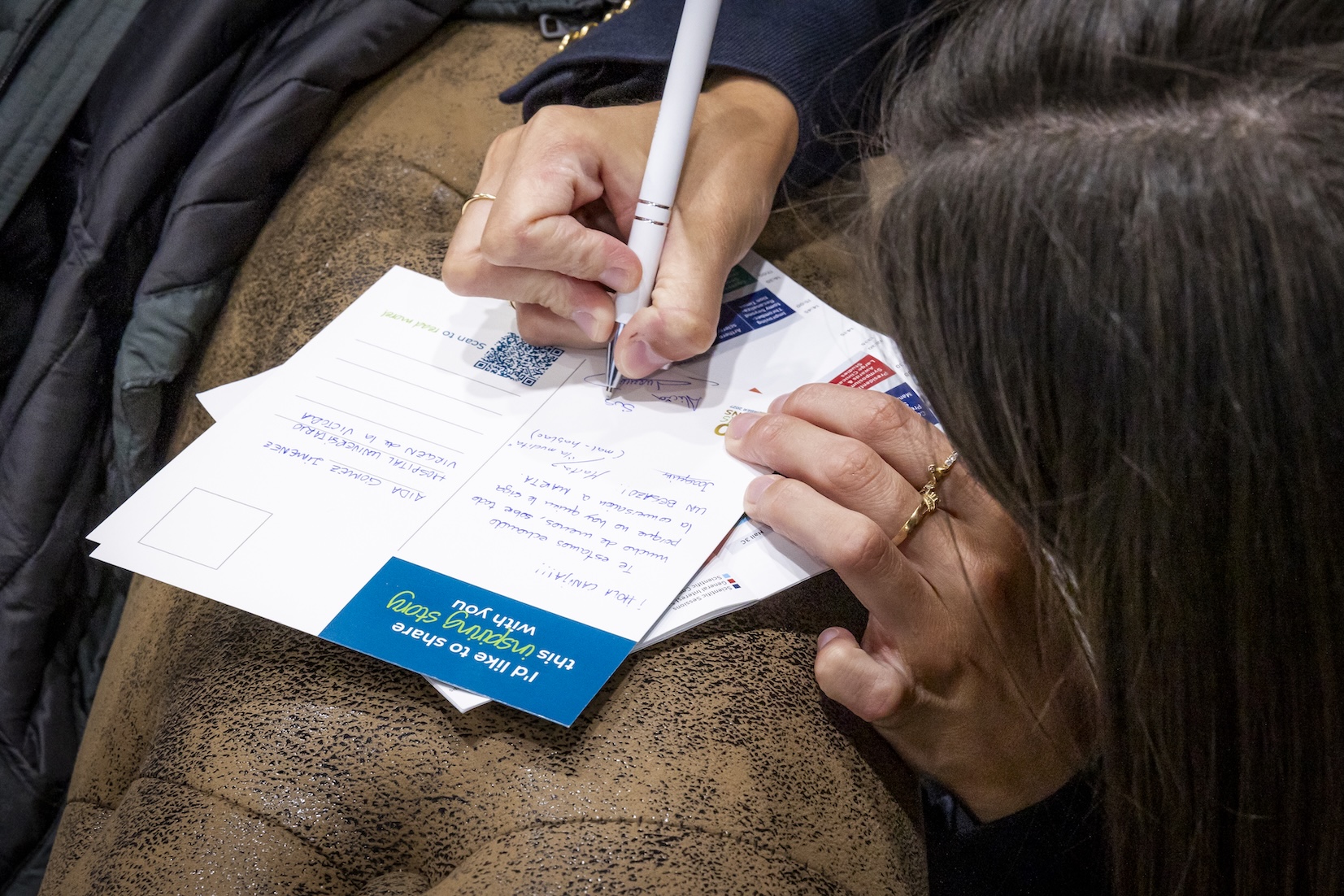

Krátko po 8:00 v utorok 28. februára, len štyri týždne po prvej návšteve, dostala Daiana správu WhatsApp, ktorú okamžite zdieľala s anjelskými konzultantmi na celom svete. „Buen día Daiana!“ sa správa začala. „Hoy cerca de la madrugada... Primera trombóliáza v nemocnici.“

Nemocnica Zenón Videla Dorna trombolyzovala svojho pacienta s prvou apoplexiou na úsvite.

Pacient bol 61-ročným návštevníkom, ktorý prechádzal cez San Miguel del Monte, keď mal mozgovú príhodu. V mnohých ohľadoch bol šťastným mužom, pretože len 30 minút po nástupe príznakov prišiel do jedinej nemocnice na kilometre, kde mohol byť liečený trombolýzou. Ošetrili ho do 60 minút od jeho príchodu a dosiahol pozoruhodné zotavenie.

„Bolo to dôležité,“ hovorí Dr. Girolimini, „pretože bol mechanik, niekto, kto pracoval s rukami. Bolo dôležité, aby on aj my pracovali.“

Dr. Girolimini tiež stále pracuje. Ak chcete skrátiť čas potrebný na vytvorenie ihly, začnite kampaň na zvyšovanie povedomia o cievnej mozgovej príhode, začnite výskum príčin cievnej mozgovej príhody špecifických pre danú lokalitu, rozšírte ich služby do okolitých miest, začnite budovať regionálnu sieť cievnej mozgovej príhody a presvedčte ostatné nemocnice, že sa to dá urobiť.

Nie je to až také ťažké, hovorí tým, ktorí neliečia pacientov s cievnou mozgovou príhodou napriek tomu, že na to majú zdroje. „Zorganizujte sa. Je to povinnosť.“